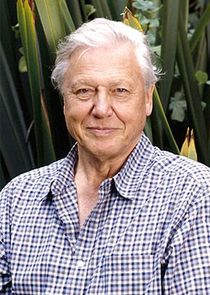

In the penultimate episode, David Attenborough looks at monkeys. This group started its life in the tree-tops and this is where we join the capuchin, whose acute vision and lively intelligence helps them findclams in the mangrove swamps of Costa Rica and crack them open on tree-anvils. The swamps are also full of biting insects, but the monkeys rub themselves with a special plant that repels them.

In the forests of South America, we see how different species of monkey can live alongside one another by having slightly different diets. The saki is a living nut-cracker, the spider monkey uses its tail to reach the ripest fruit and the pygmy marmoset is so small that even the outermost twigs of the canopy can support its weight as it stalks insects. David even meets an owl monkey, a shy and mysterious creature with huge eyes that feeds at night to avoid competition with the others.

Hanging from a rope high in the forest canopy of Venezuela, David watches the stunning red howler monkey as it uses excellent colour vision to pick the best leaves. Although colour vision evolved to detect leaves and ripe fruit, it allowed the monkeys to become the most colourful of all mammals. The scarlet face of a uakari is dazzling, the long moustache of the emperor tamarin is striking even from a distance, but the most beautiful colours are found on the guenons of west Africa that use intricate patterns on their faces to send social messages.

These guenons are under constant threat from eagles, leopards and chimps, but different types of guenon join forces with other monkeys. They travel together in an extraordinary anti-predator alliance based on shared vigilance and a remarkable degree of vocal communication.

But the most complex relationships to be found in the monkeys are between animals living in the same group. And the larger the group, the more individuals with good social skills will thrive. In Sri Lanka, we watch male toque macaques battle for mates and see how brain can triumph over brawn.

Ten million years ago, a change in climate allowed one group of African monkeys to move down from the trees and on to the grasslands. But living on the ground brought an increased risk from predators, forcing baboons to live in even larger groups - and this put an even greater emphasis on social skills. Life on the ground also opened up new hunting opportunities - the hapless flamingos of Kenya are now on the menu.

Several miles above the savannah, in the highlands of Ethiopia, we meet the monkeys that live in the largest groups of all - geladas. Groups of 800 drift across the high plains like herds of wildebeest. It is hard for so many animals to stay in contact by grooming, so these monkeys have another way of communicating - they chatter to each other using the most complex sounds made by any mammal yet studied, except for ourselves. So while monkeys in the treetops have rich and varied social lives, it is those that came down to the ground that developed the most complex and communicative societies of all - a fact not without significance for our own ancestry.

No comments yet. Be the first!